Most basements show some signs of leaking and cracking. Through the years, problems with water, poor soils, grading, drainage and possible settling affect the integrity of a basement. We should know how to recognize small problems and then take steps to avoid large ones. Maintenance or simple repairs often eliminate the need for major expenses.

Let’s talk about typical basement cracking and the keys to understanding whether the problem is serious. As you review the text, refer to basement wall sketches that depict various problems.

We will not focus here on the basics of basement construction, systems and maintenance. For maintenance information, take a good look my article “Keep Your Basement Dry” or the basement chapters in my book How To Operate Your Home, second edition, which review the basics of basement construction, drainage systems, sewer systems and routine maintenance every homeowner should perform.

The Basic Basement Problems – Cracks and Seepage

Most damage to basements occurs slowly, over many years, and homeowners may not notice a problem until there is a water leak or a major crack and wall movement. Homeowners should take some time to inspect the basement and its environment. A little common sense and simple maintenance will prevent potentially serious problems. Knowledge about changes in the foundation’s condition is essential to recognizing problems. Remember, water is the real threat to any foundation.

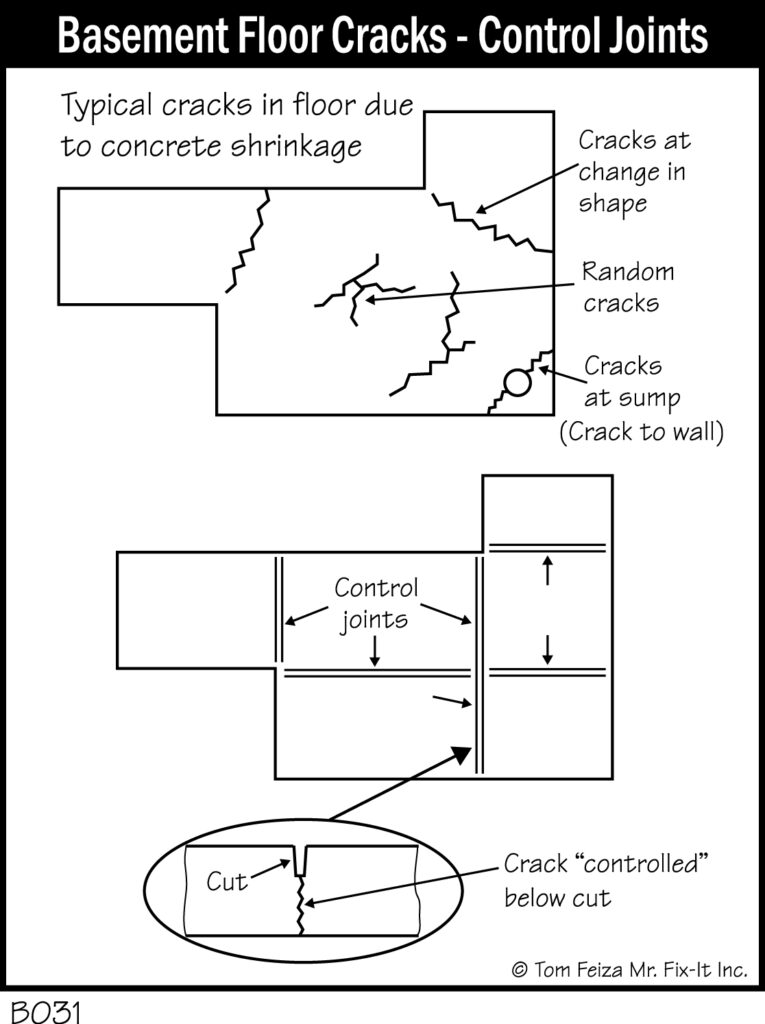

Cracks are signs of an overload or excessive stress in a wall. As homes get older, cracks have a better chance to appear. Excessive displacement, continuing movement, settlement, and certain combinations of cracks are real problems we will discuss. The exception – those little hairline cracks that appear in floors and walls – are often caused by shrinkage and are not a concern since they are just cosmetic in nature.

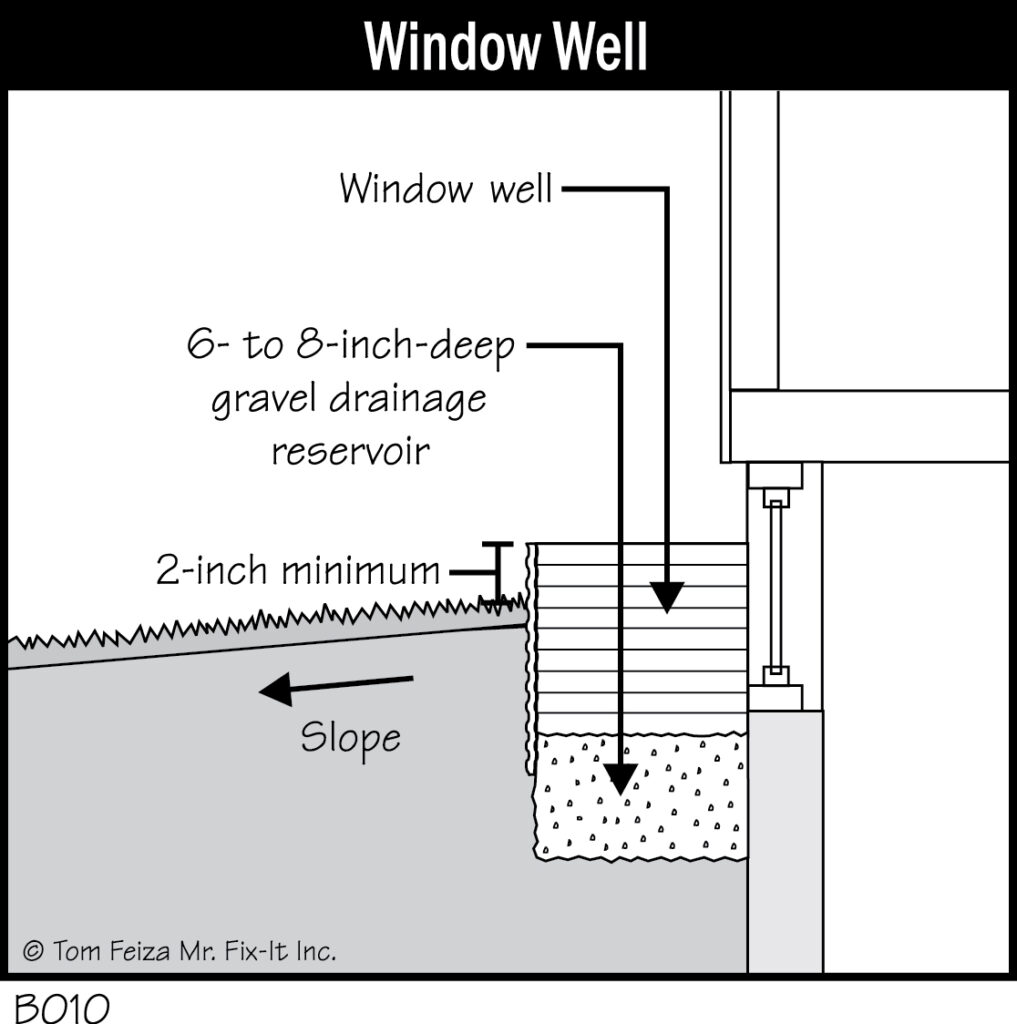

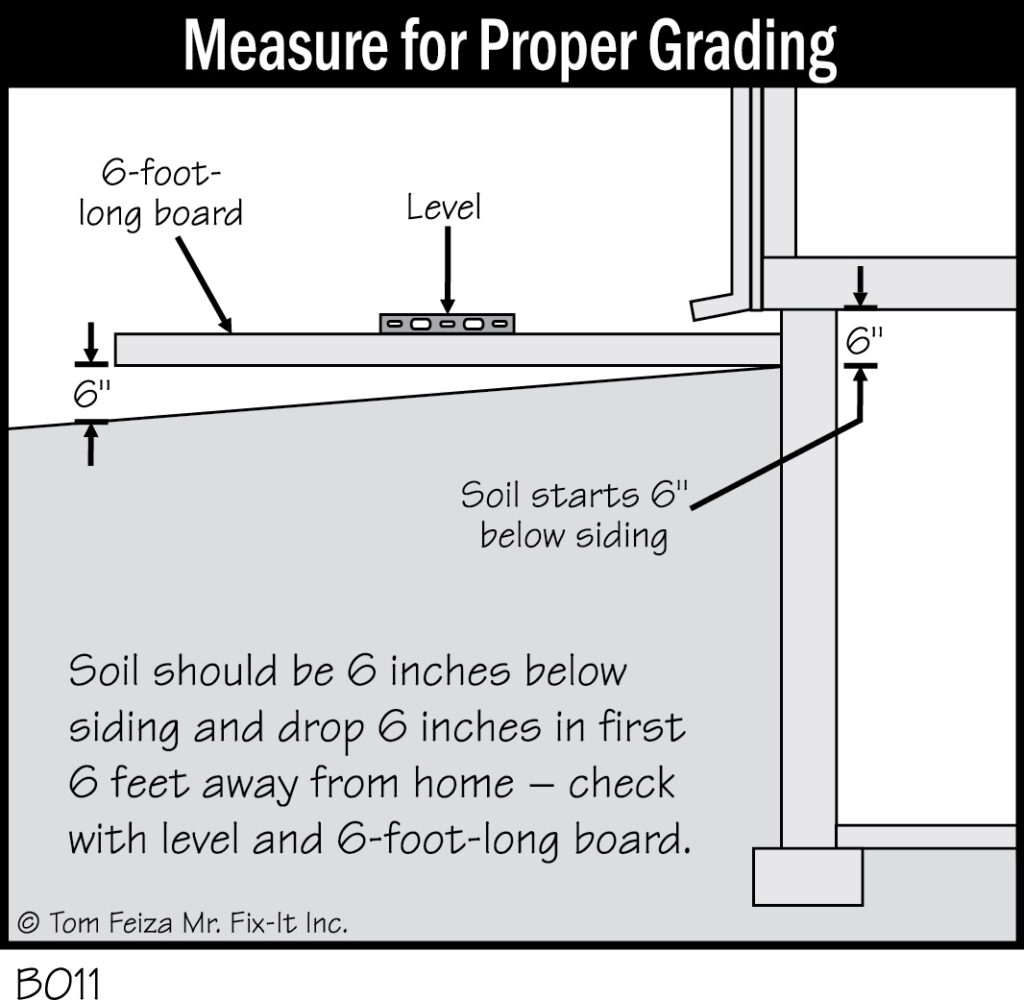

Seepage, another common problem, may occur in combination with cracks. However, seepage problems are not always directly related to cracks. Seepage is often caused by surface water reaching the exterior of basement walls. Ineffective or poorly maintained drainage systems can also allow seepage. If seepage and leaks continue after correcting drainage and water removal systems, they need further investigation – something that I cover in detail in “Keep Your Basement Dry.”

Remember: a dry basement may have serious cracks and structural problems, while a leaky basement may be structurally sound. Cracks, movement and leaks do not always go hand in hand. Surface drainage issues often cause seepage problems. Wet soil from poor surface drainage causes leaks, and pressure from the wet soil can cause cracks and structural failures.

Cracks – The Good and the Bad

How can you determine whether a crack is good or bad? There is no easy answer. It depends on the type of construction and the history of the basement. Understanding basement cracks requires recognizing basic types and knowing how they occur. Take a good look at the sketches of various types of cracks. Which ones does your basement have?

What distinguishes a minor crack from a major problem? The key is often the amount of wall movement. Any movement over 1/2 inch signals a potentially serious problem. Any long horizontal crack at the second or third mortar joint combined with step cracks and inward movement indicates a problem. While step cracks near windows and corners are often not serious, if they are combined with floor cracks, shear, or vertical cracks, you should be concerned. Sound confusing? It is; read on.

Typical Basement Construction

A typical basement or foundation is constructed to support the home and to resist the movement of frost. Often, in heating climates, basements are constructed because the foundation must extend below the frost line – and once you dig down four feet to get below the frost line, a full-depth basement makes sense. In mild climates there is little or no frost, and the foundation often consists of a concrete slab on grade or a crawl space.

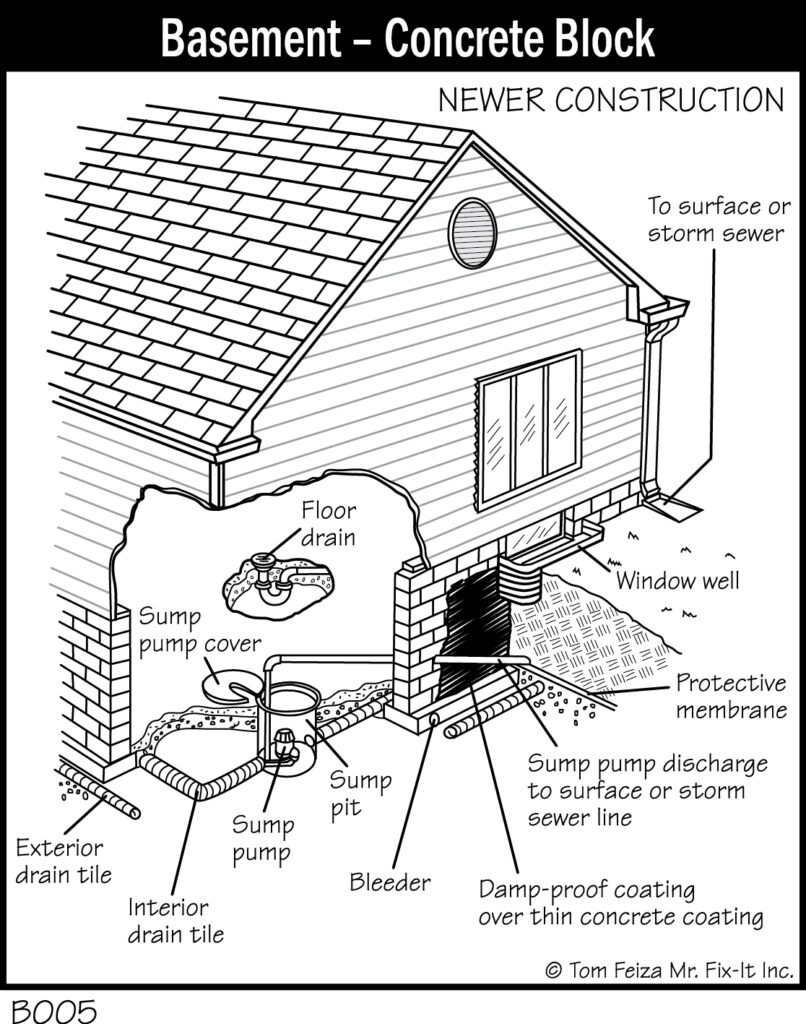

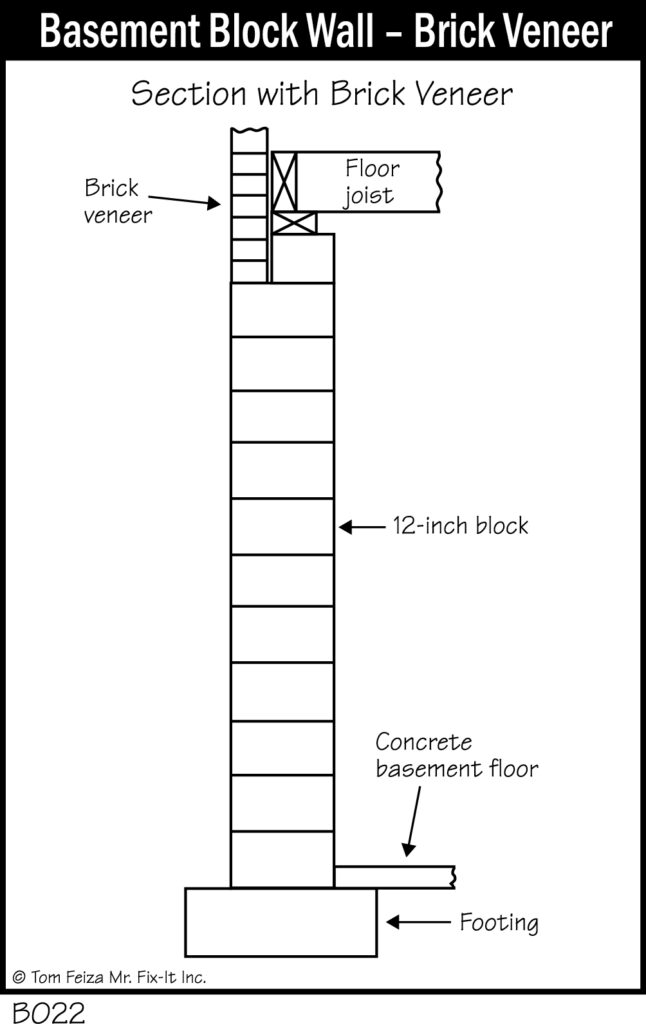

A typical basement is constructed of a footing or footer that supports the basement walls and floor. The footing must rest on solid or undisturbed soil. The wall may be constructed of cement block, poured concrete, brick, stone or tile. In the past 80 years, most foundation walls have been constructed of cement block or poured concrete. The floor is poured concrete supported on the edges by the footing and in the center by compacted gravel.

In areas with soils that don’t drain well, such as clay soil, a drain tile system is often installed. Drain tiles (today “tiles” are made of perforated plastic tubes) are laid outside the footing and inside under the floor. Bleeders are installed through the footing to allow water to pass from the outside to the inside. The inside tile is then connected to a sump pump crock and sump pump. As water drains into the crock and the level rises, the pump turns on and removes the water.

Block or Poured Concrete Walls

A block or cement block wall is laid up like a brick wall. Mortar is used to set the block in place and bond the block together. Today, a block is called a concrete masonry unit (CMU), and blocks are built to specific engineering standards. Most blocks used in basements have a hollow core. The term block also refers to a cinder block – old block that may have some cinder or burnt coal content.

A block basement wall easily supports the weight of a home. Block is very strong in compression. However, block walls, if subjected to horizontal pressure, have less strength than poured concrete. Some block walls are reinforced with special metal bars and grids built into the mortar joints for increased strength.

The basement walls can also be made of poured concrete. These walls typically are stronger against horizontal pressure, and they easily support the weight of a home. The construction looks the same except that poured concrete is substituted for cement block. The texture inside the basement may be smooth or may be a decorative brick texture.

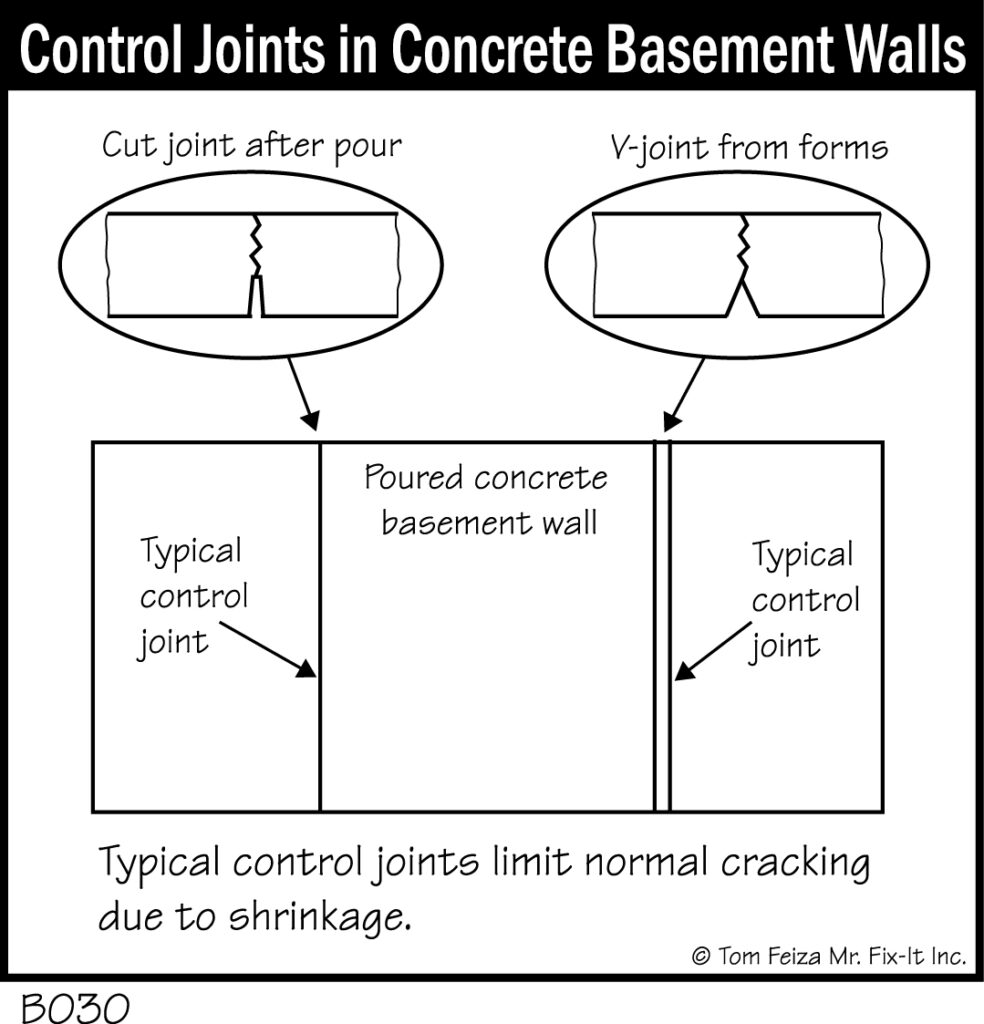

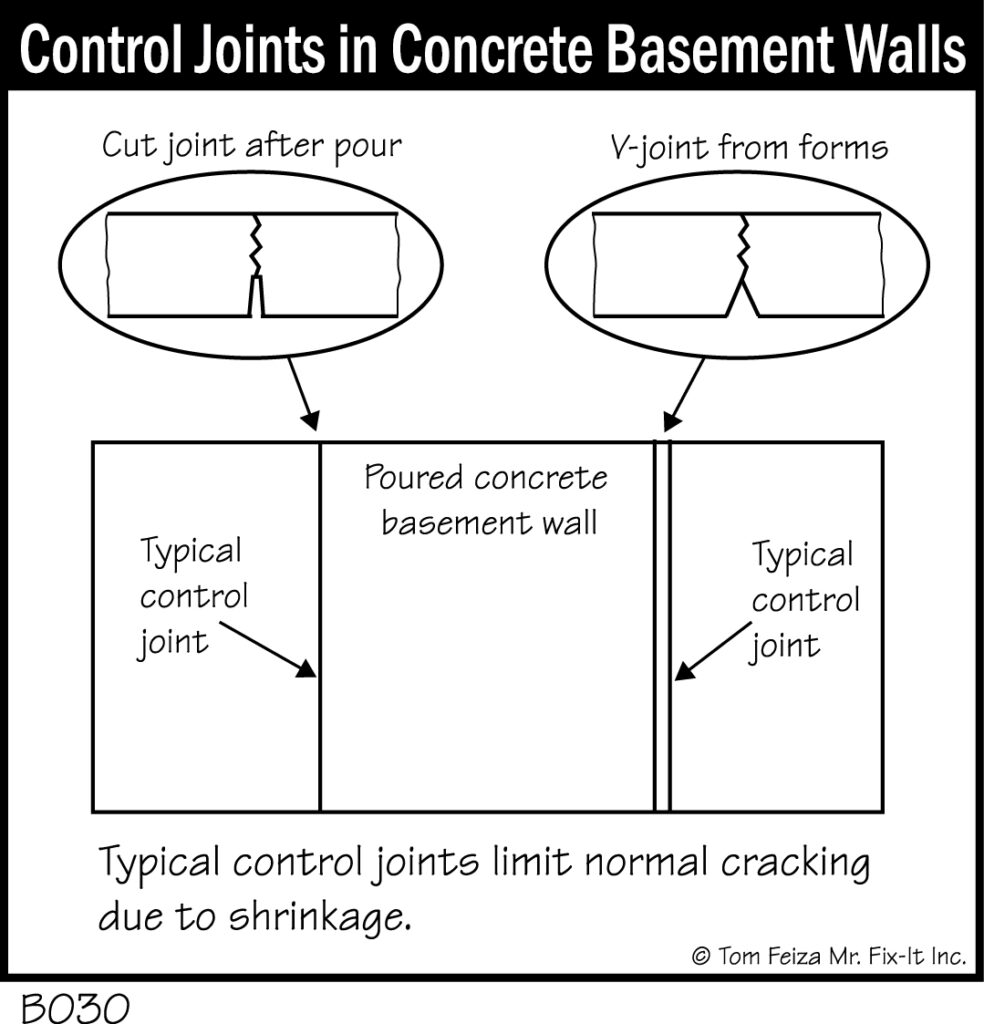

In newer construction, grooves are often cut into the poured concrete wall or formed in the wall to control cracking. We know the walls will shrink and crack, because poured concrete shrinks about 5/8 inch per 100 feet if the mix is properly controlled and weather conditions are correct. With a poor mix, extra water or poor weather, the wall may shrink even more. The grooves allow cracks to occur in a controlled fashion.

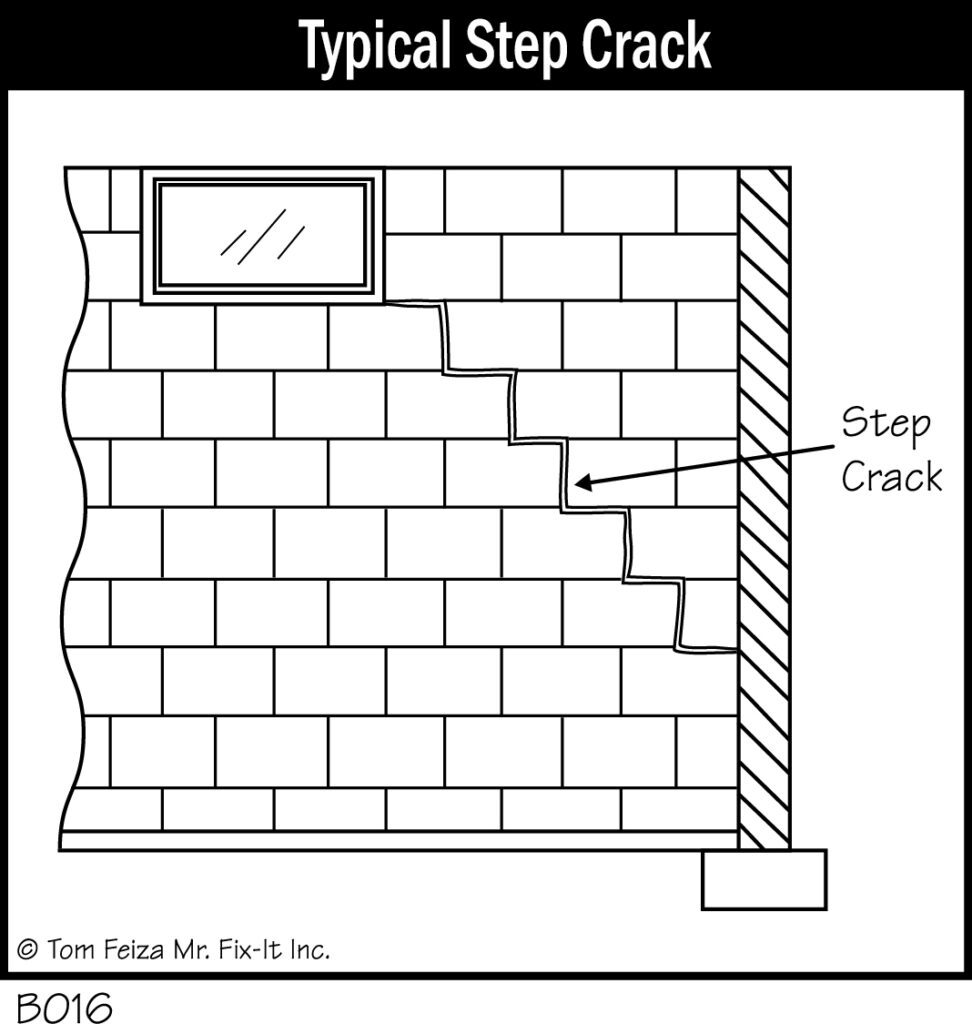

Step Cracks

Step cracks, stairstep cracks or stepping cracks all refer to cracks that follow the mortar joints in a block wall. The cracks step up or down along the mortar. In many cases this type of crack is caused by minor movement of the footing, shrinkage or wall movement, and by itself is not a major cause for concern; but wide cracks or step cracks combined with other cracks and movement indicate a problem.

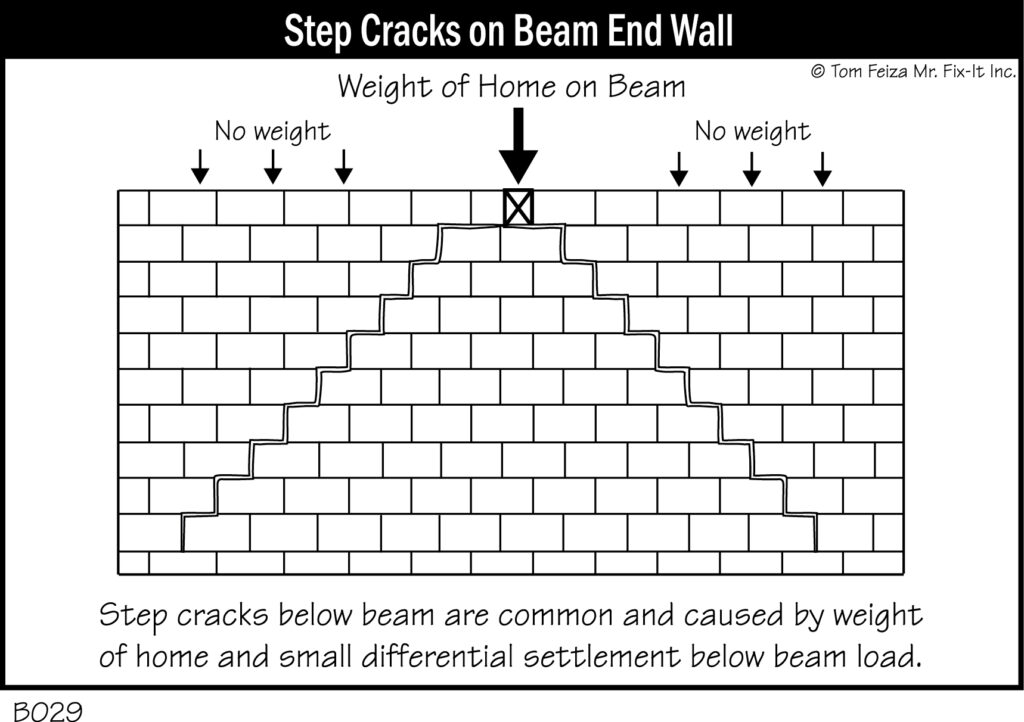

Step Cracks at Windows and Beam Ends

Step cracks will often occur at the weak point of a wall – around window openings. Step cracks are common at “beam-end” walls. At the beam-end wall, the beam transfers a large point load to the wall. The load often creates step cracks down and away from the beam as the footing settles ever so slightly. Block walls do not like to move; they do like to crack.

Step Cracks Combined With Horizontal Shear

Combinations of cracks often indicate a more serious problem. Step cracks may be found with horizontal cracks, vertical cracks and wall movement. A combination of cracks needs a professional review.

Vertical Cracks

Vertical (up and down) cracks can be caused by simple shrinkage of materials. These cracks often occur in the control joints of poured walls. They appear as hairline cracks in mortar joints and through blocks in a cement block wall. Some vertical shrinkage cracks in poured concrete can be up to 1/8 inch wide. Cracks in block walls should be very narrow without horizontal movement.

Vertical cracks are an issue if they are wide, tapered from top to bottom, or found in combination with other cracks. They can occur because of settlement, wall movement or tipping walls. Vertical cracks also occur if a wall is pushed in and breaks away from the adjacent corner or surface. Vertical cracks with horizontal or shear movement at the crack always indicate a problem.

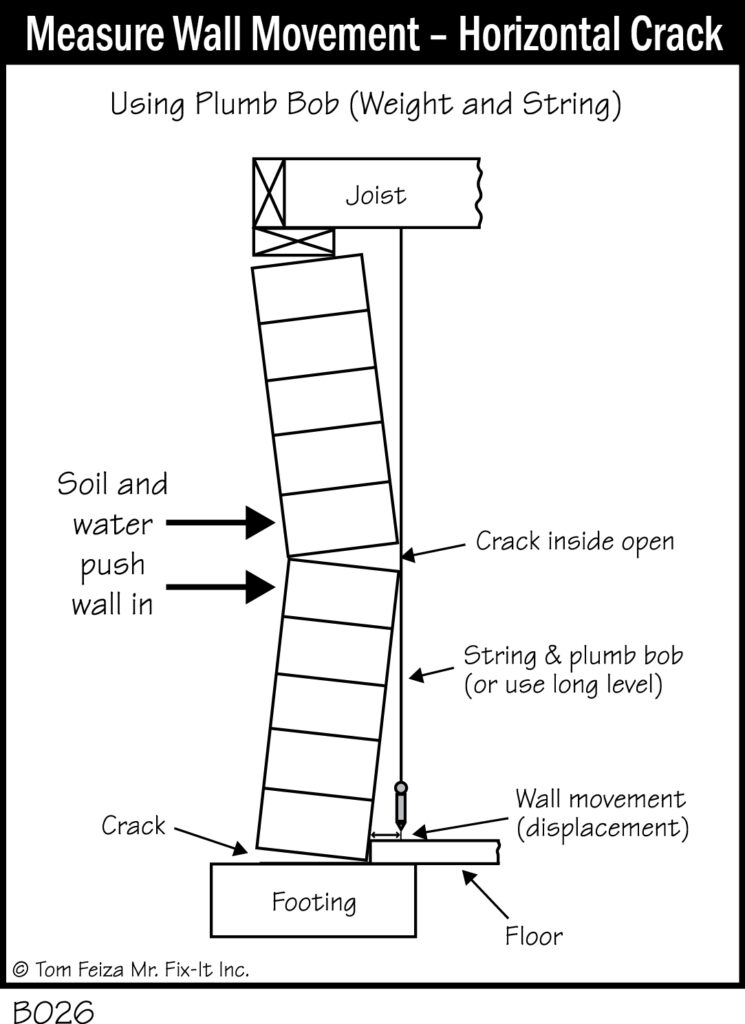

Horizontal Cracks

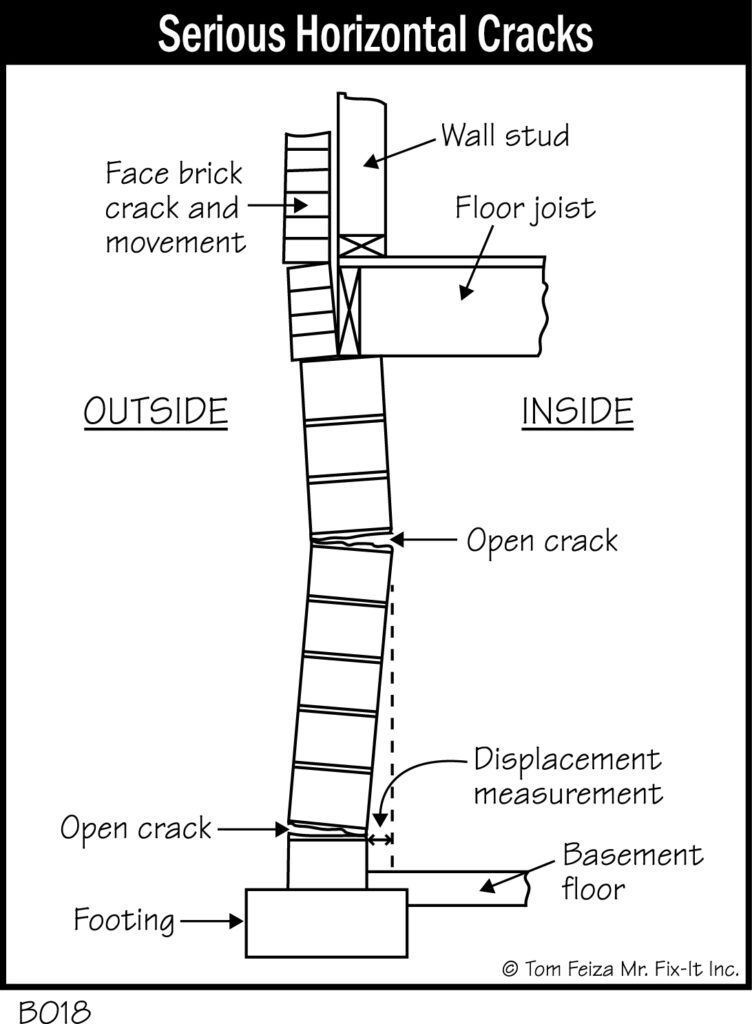

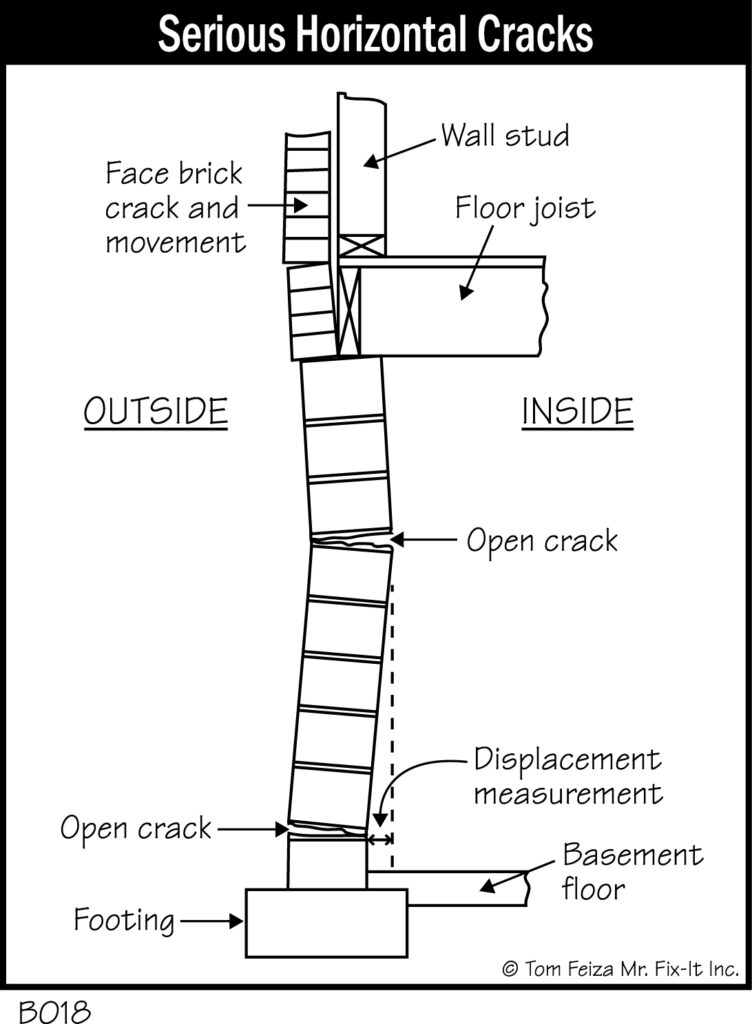

Horizontal (left to right) cracks can appear at the mortar joints in block walls. They indicate that the wall is displaced horizontally. As the wall is pushed in, the joint opens up inside the basement, and a similar crack will occur outside near the base of the wall. Horizontal cracks are caused by wet soils, poor maintenance of surface water, and frost. Horizontal cracks in block walls always need to be taken seriously. A horizontal crack combined with step or vertical cracks indicates a problem. When the crack is over 1/8 inch wide and there is horizontal wall movement of 1/2 inch or more, the problem needs to be addressed.

Horizontal cracks will often change seasonally. When there is water in the soil, the soil may expand – a common trait of clay soils. When the wet soil expands, the wall may be pushed in and the horizontal crack may open further. When the soil dries, the crack may close. Frost in exterior soil causes similar movement and cracking as the frost expands the soil.

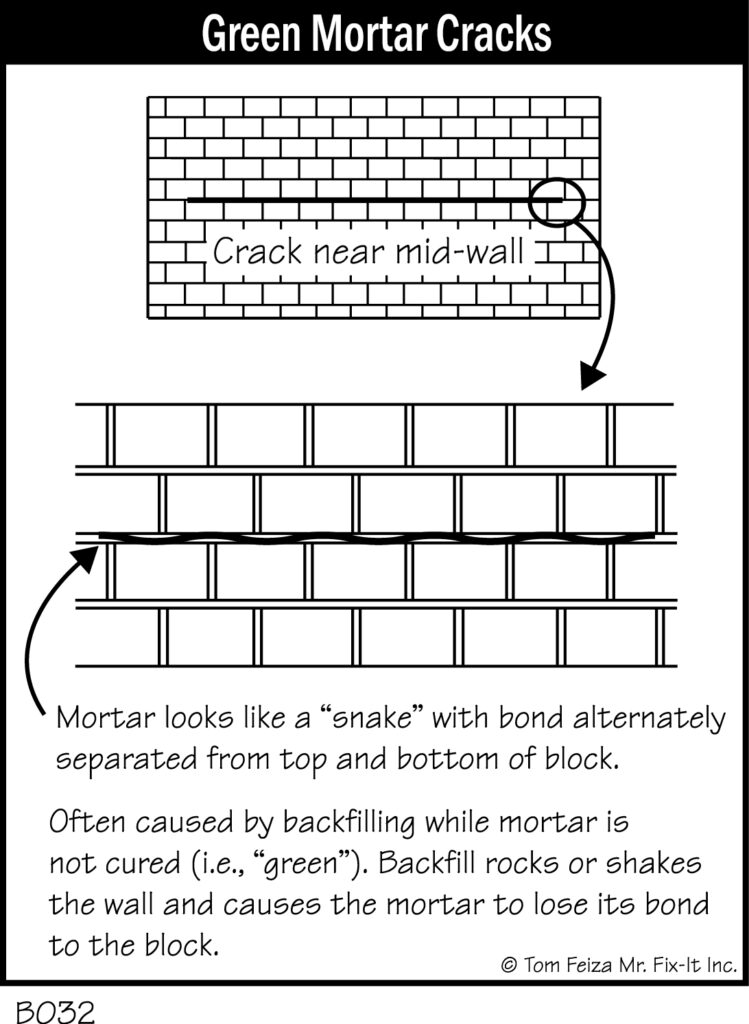

Green Mortar Horizontal Cracks

One type of horizontal crack may not be a concern if there is little movement and the mortar in the joint of the crack moves up and down inside the crack – sticking to the top block and then the lower block. It will look like a snake of mortar in the open crack. This crack is often called a “green mortar crack,” and it probably occurred during construction of the basement.

When a home is built, the foundation is constructed in a hole or excavation. As soon as the block wall is laid, back-fill may be added to the outside of the block walls because construction needs to move ahead. If the walls are not braced from the inside or if a large bucket of dirt hits a fresh or “green” wall, the wall can be bounced out of plumb and the joint cracks open. Because the mortar is not fully cured (“green”), it is still partially plastic, and it pulls away from the block.

Green mortar cracks are serious if combined with other cracks, if they continue to open up, or if there is significant displacement of the wall.

Measure Displacement

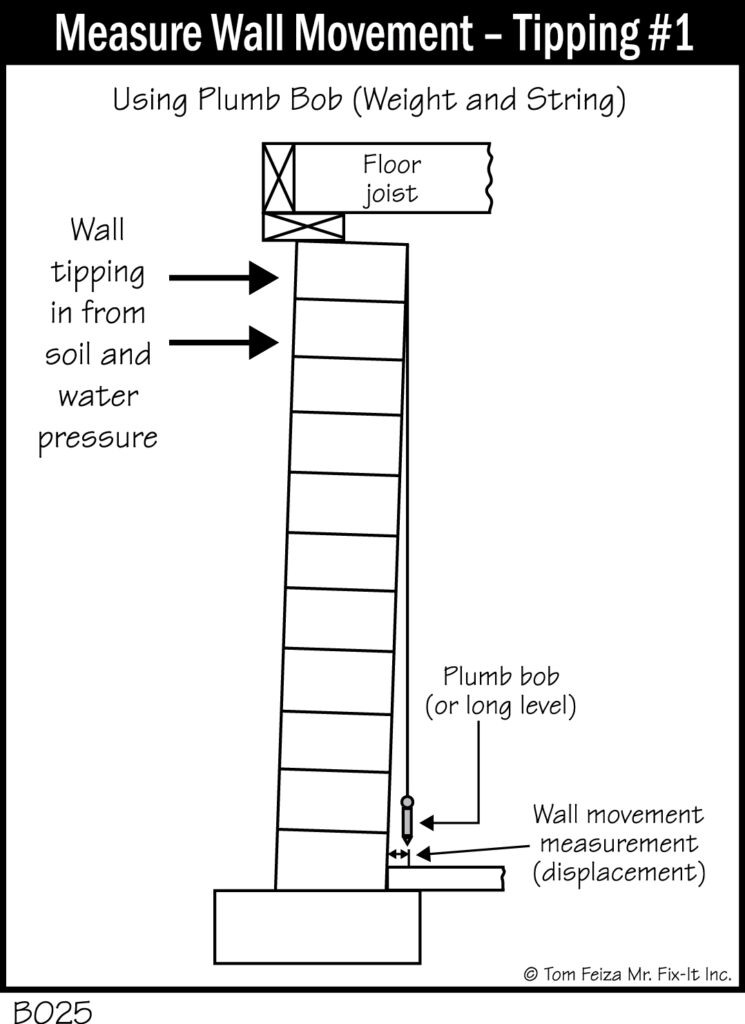

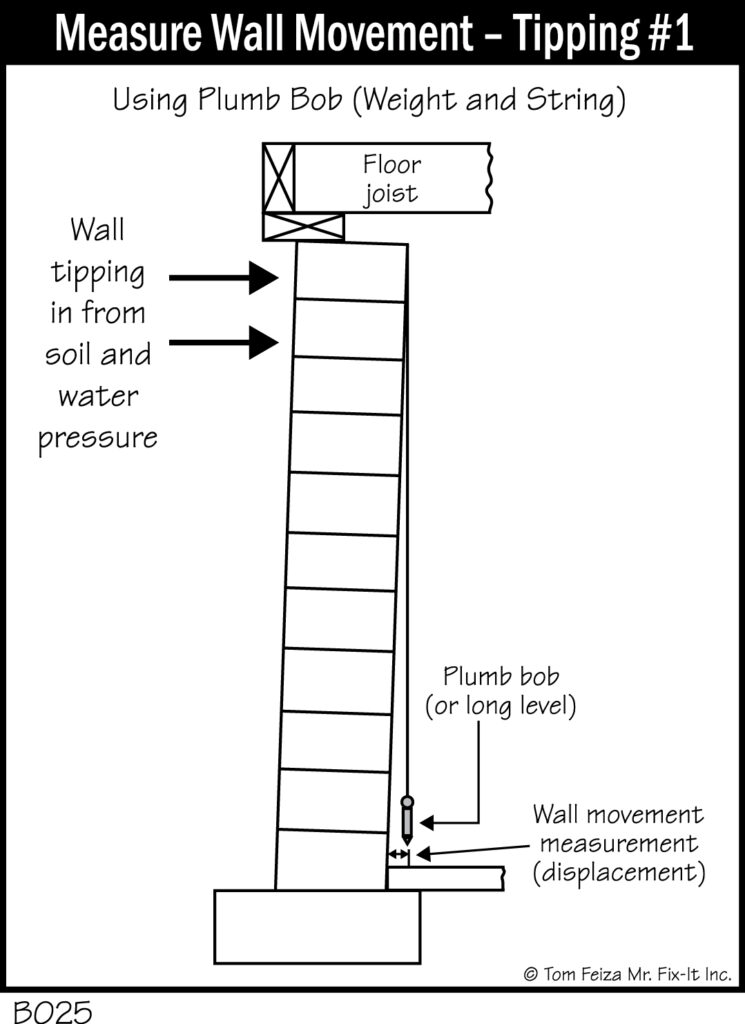

The displacement or movement of the wall is a critical measurement to determine whether a wall is in jeopardy. Measurements can be made with a 4-foot or longer level, a laser level or a plumb bob. The key is to measure over the height of the wall and then compare measurement to the corners.

In many cases, corners don’t move because the block is “woven” together in a strong joint that resists horizontal movement. The corner of a concrete wall is also very strong. If the wall is displaced in relation to the corner, there may be a problem. If the corner is tipped and the whole wall is similarly tipped, the wall might have been built out of plumb. As the block wall was built, a string was pulled from the corner to align the block of the wall; if the corner is tipped, the wall will be tipped.

The plumb bob measurement makes the movement easy to visualize. The weight at the bottom of a string holds the string “plumb” or vertical, and you can measure from the vertical string back the wall. If you find cracks and displacement over ½ inch, you should start to question the stability of the wall and consider possible repairs.

Wall displacement may also be referred to as deflection. However, technically “deflection” usually describes materials that move under load or stress and then move back to their original position once the load is removed.

Multiple Horizontal Cracks

At times you may see multiple horizontal cracks – cracks that occur in several mortar joints above and below each other. This is often the sign of ongoing movement or movement on several occasions. This is reason for concern.

Combination of Cracks

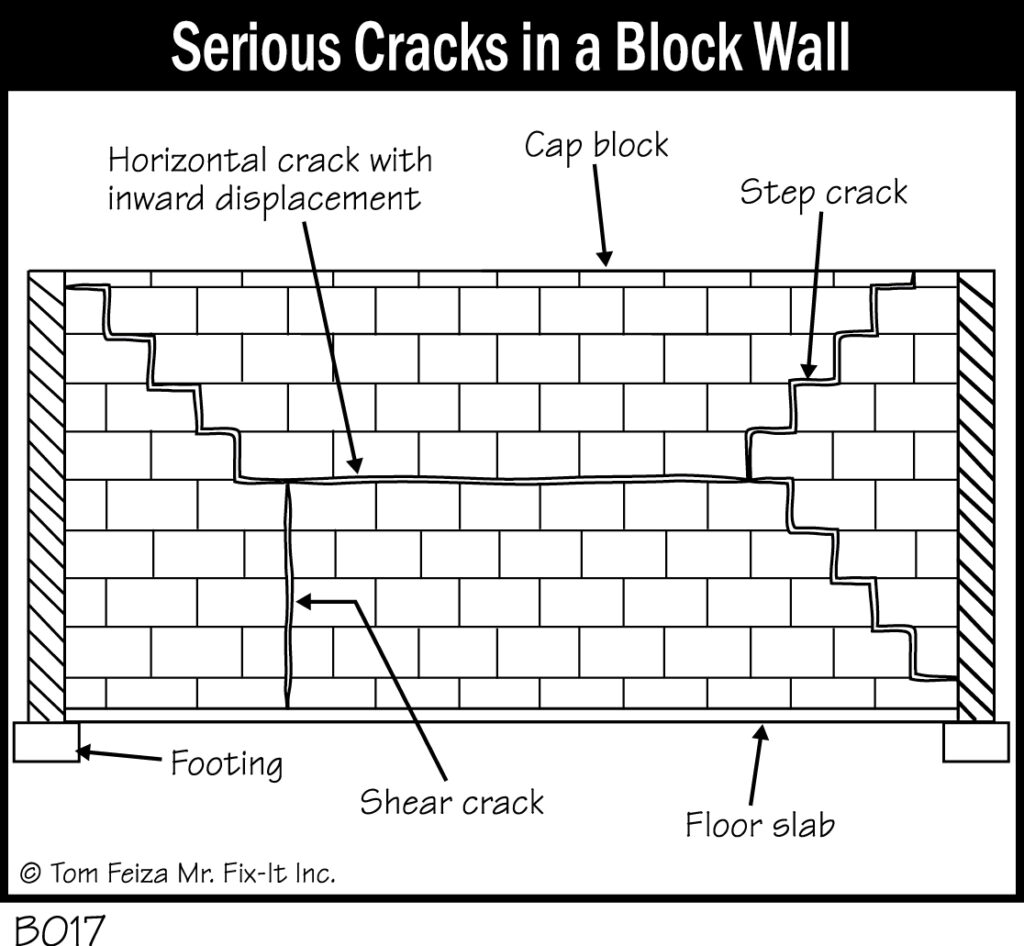

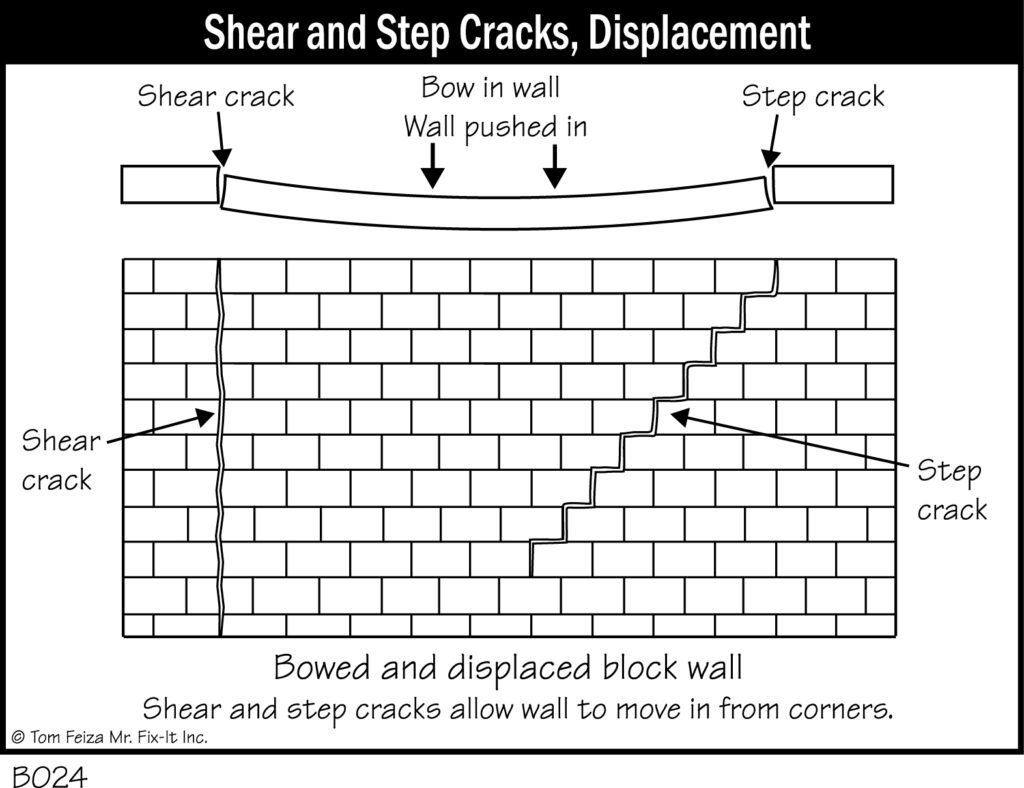

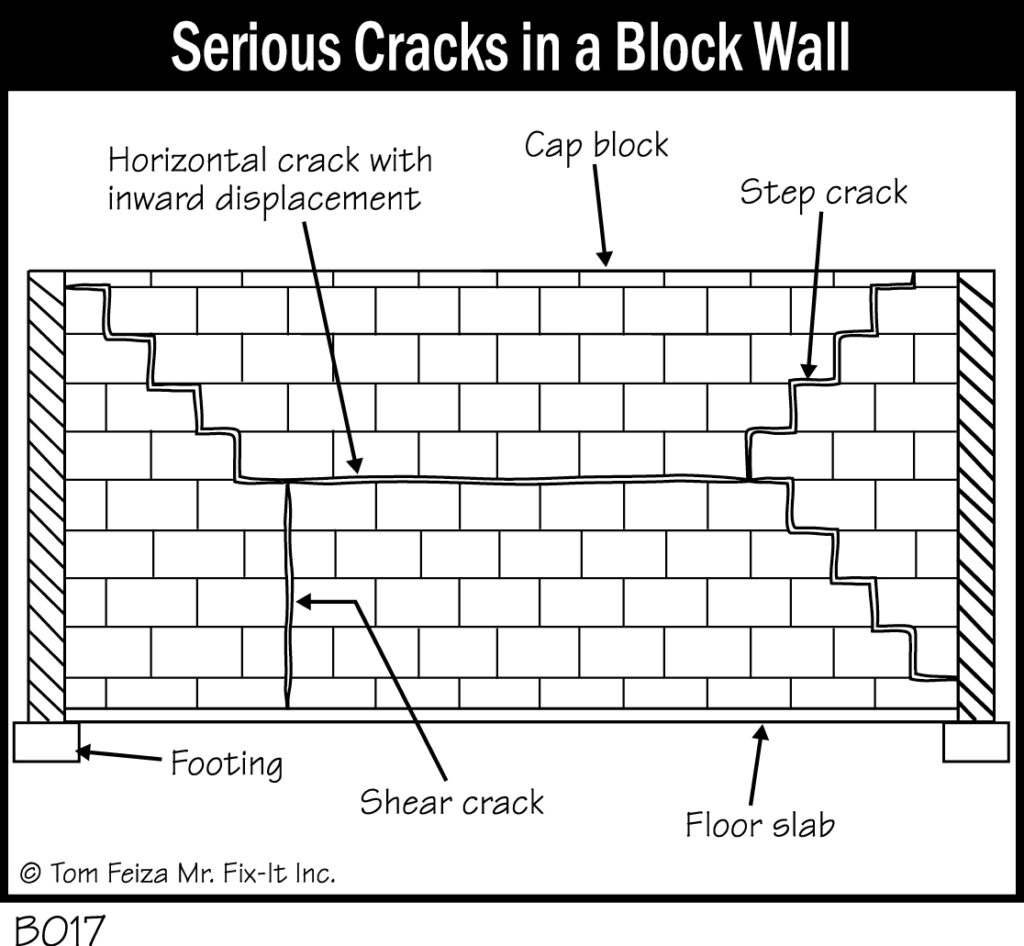

All combinations of cracks are cause for concern. Illustration B017 depicts a wall with serious cracks and displacement. As the wall is pushed in, the horizontal cracks open. With more movement, the wall breaks away from the corners, resulting in step cracks and vertical cracks. The corners are stable, while the wall breaks away. This type of movement and cracking typically occurs in a block basement, not in one made of poured concrete.

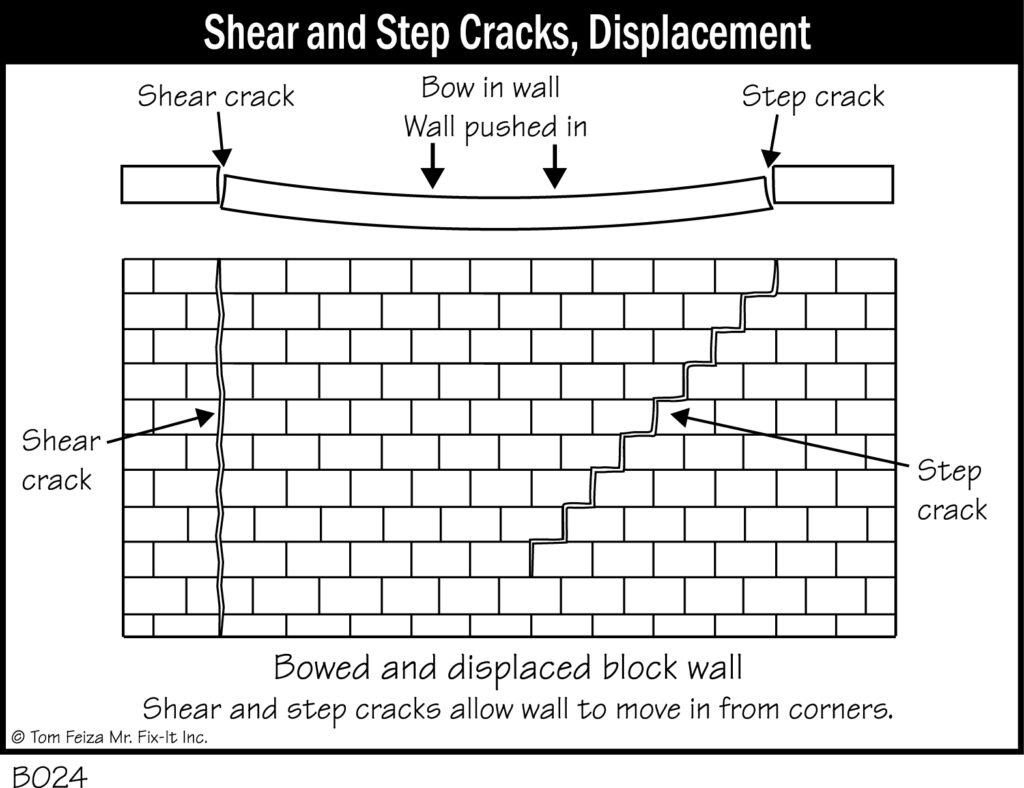

Illustration B024 depicts a wall with a serious inward bow. As the wall moves inward, the wall splits away from the adjacent surface with a vertical shear crack and a step crack. The illustration shows the top view and the displacement of the wall. On the outside, vertical cracks will occur in joints near the corners.

Settlement and Footing Movement

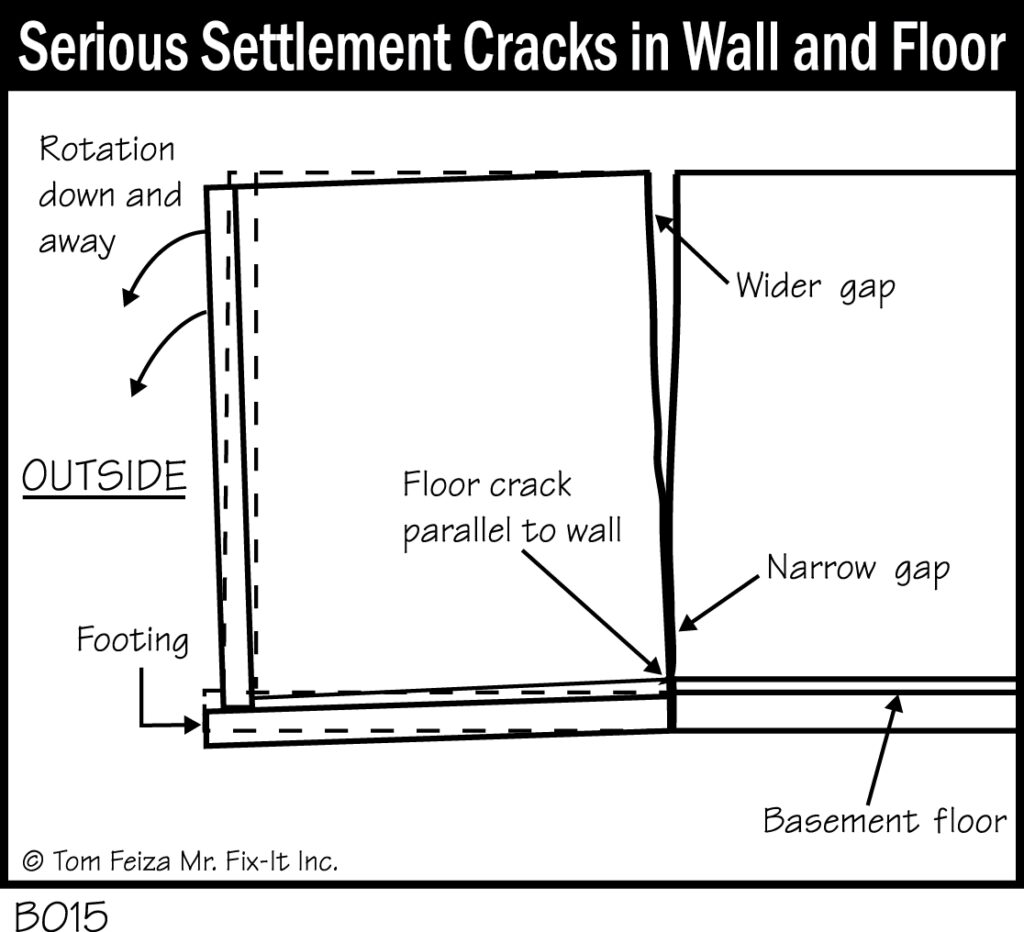

Settlement cracks are caused when the footing supporting the home moves downward or tips. Illustration B015 depicts a footing that has settled, creating a crack in the wall above the settlement. The crack is open at the top and tighter at the bottom. There will often be a crack in the floor where the footing has started to drop.

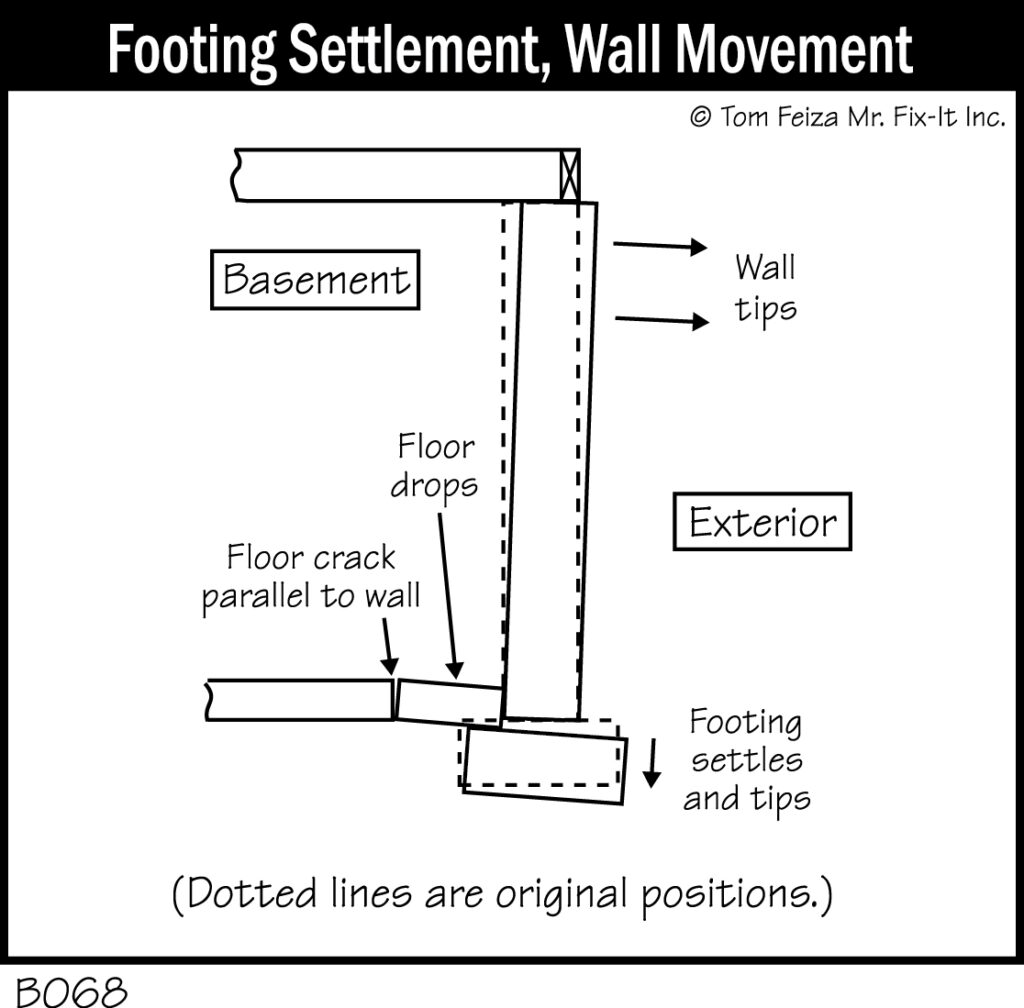

Illustration B068 shows a footing that has settled and tipped away from the foundation. In this case, the wall tips outward and may have step or vertical shear cracks. There will often be a floor crack parallel to the footing movement, and the floor may be raised or dropped. There may be shear or lifting at the floor crack.

With serious settlement, crushed lead plumbing pipes may be visible where they enter the concrete floor. The floor may also be cracked and heaving with significant displacement. Settlement may also result in a corner that tips away from the foundation walls.

All significant settlement issues must be addressed by a professional and often require an engineered design solution. Work may require soil testing and a special pier design to provide support to the footing from stable soil below.

Displaced Walls – Tipped, Shear, and Slide

Walls can also move with little signs of cracking. A wall that tips in over time (see illustration B025) will be found by measuring for displacement and movement relative to the floor framing. This can happen in block and cement walls. Severe movement creates vertical or step cracks that allow a section of wall to break away. With minor movement, the problem can occur without creating cracks, and it is hard to detect. The framing sill plate could be split or could slide on the top of the wall.

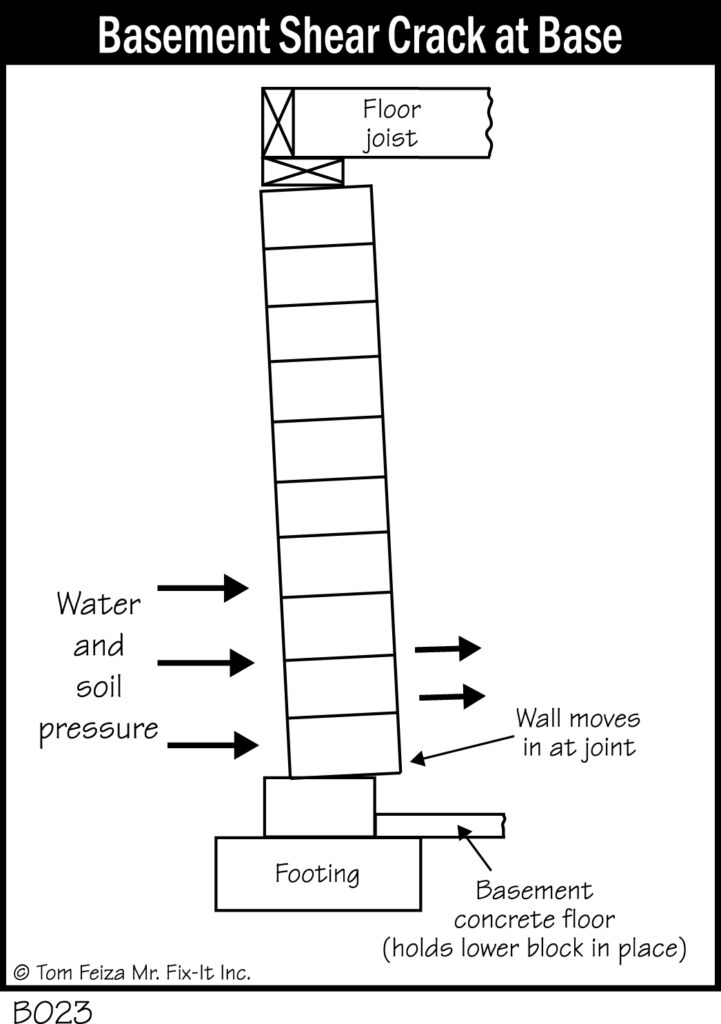

Walls can also be pushed in at the base when there is slip or shear at a lower mortar joint (see illustration B023). In this case, soil pressure forces the wall in and a lower block joint is broken or sheared. This is often hard to see with a cursory look, but it is a serious issue because the wall has lost its ability to resist horizontal pressure, which is greatest at the base of the wall. The poured concrete floor is holding the lower block in place.

Exterior Signs of Problems

Brick Veneer Movement

A basement supports the brick or stone veneer on homes that we call brick or stone homes (although they are actually wood-framed homes with masonry veneer). If a basement wall has serious cracks and inward displacement, the top of the wall tips outward. As the top tips out, the brick veneer supported by the wall also tips outward. You may also see horizontal cracks in the veneer, or the veneer may be pulling away from the wood framing. You will see this movement at the end joint between the veneer and the siding. Look for additional trim or caulk filling a gap at the top of the masonry veneer.

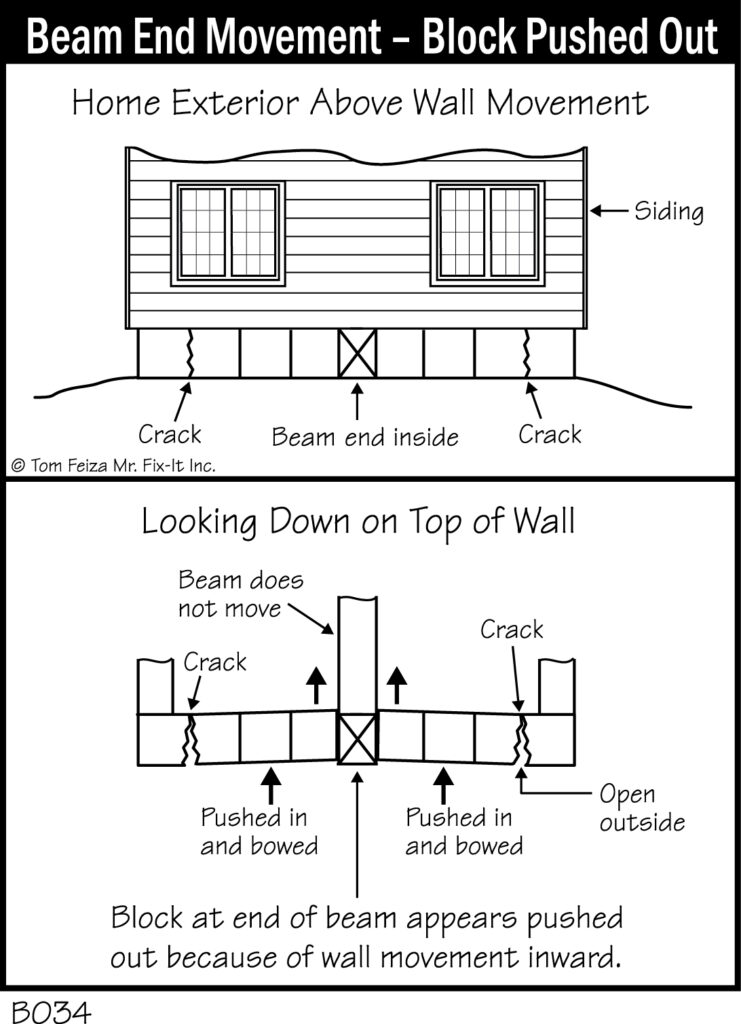

Displacement at Siding and Beam-End Cracks

Often, when a basement is pushed in, the top of the wall undergoes significant movement. You may see this movement outside the home. There will be vertical cracks at the corners where the wall breaks away from the corners. The block covering the end of the beam may be pushed out as the wall moves in, because the beam normally will not move.

You can also detect serious movement by measuring from the siding to the top of the block wall. Measure at the corners from the outer edge of the siding to the block, and then measure at the center of the wall. The increase in the measurement at the center of the wall indicates how much the wall has moved.

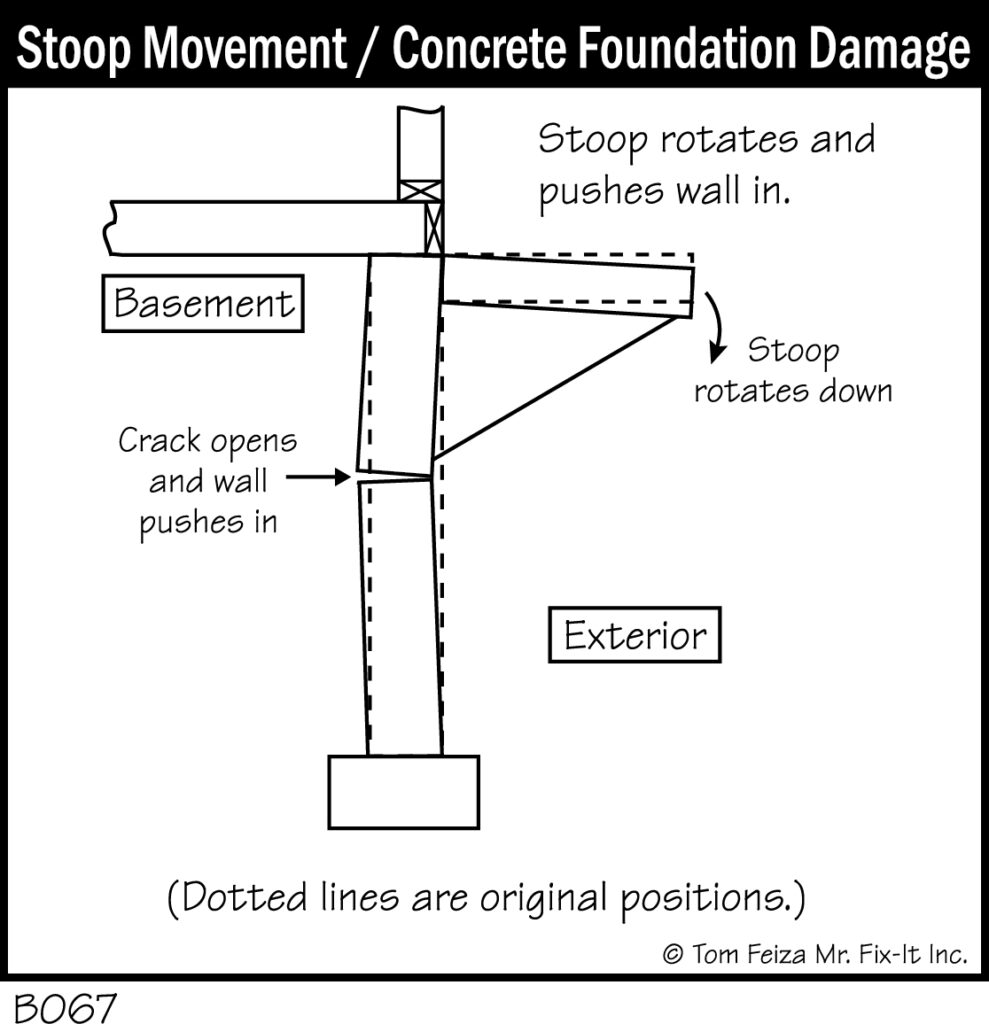

Tipped Stoops

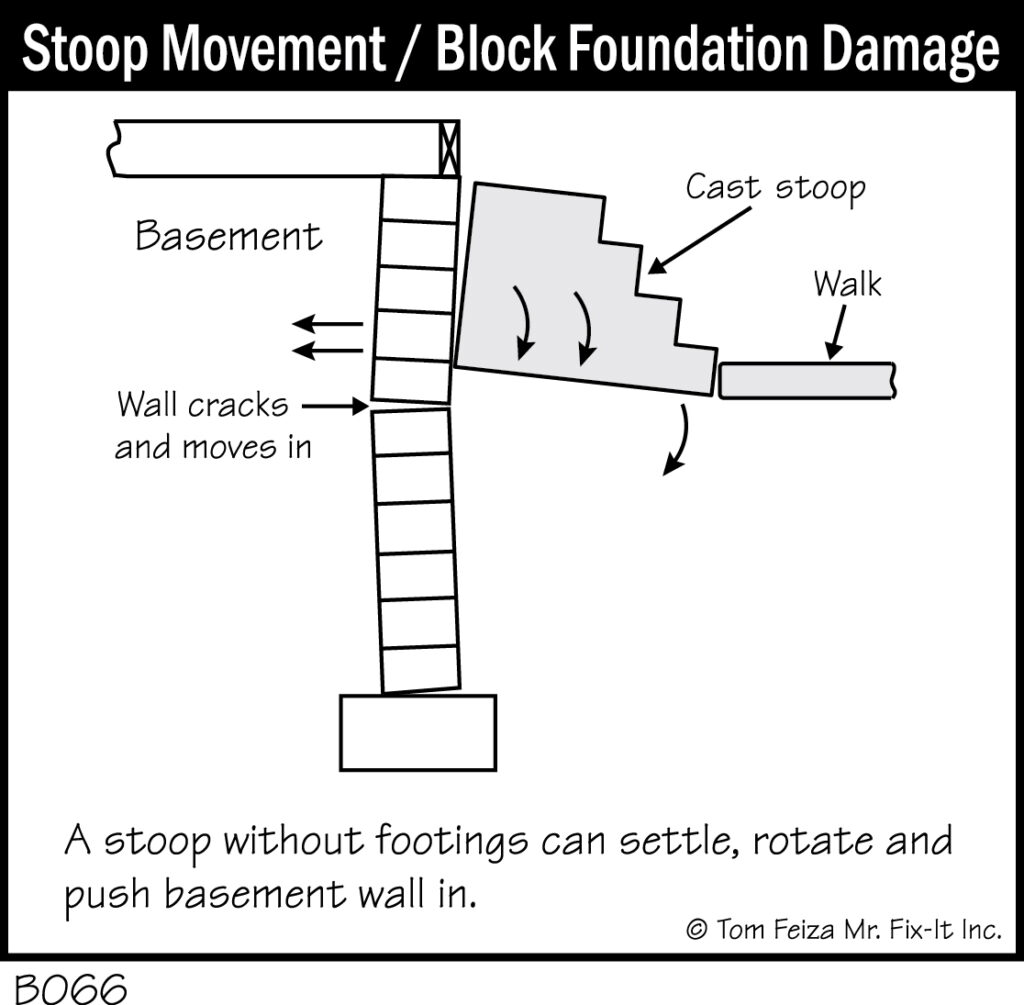

Tipped entrance stoops can cause a basement problem and often result from lack of a proper footing for support. As depicted in illustrations B067 and B066, stoop movement can crack basement walls. If the stoop tips down, away from the home, the pressure of movement can displace and crack a block wall. If the stoop support is not properly designed and executed for the poured wall, the concrete foundation wall can also crack.

A stoop that tips toward the foundation wall can also crack a block wall. When a stoop tips in, it will direct water toward the foundation wall – and this is always a problem.

Floor Cracks

Basement floor cracks are common, because concrete shrinks as it cures. Don’t be concerned with random spiderweb-like cracks or cracks that occur from an inside corner. These are often shrinkage related. Basement floors often have gaps between the floor and the wall or around the sump pump crock in a corner. Think of your basement floor as a cake mix in a 9-by-13 pan – as it bakes, it pulls away from the pan (the basement wall).

Do be concerned if the cracks are parallel to the wall and footings or if there is vertical movement associated with the cracks. Displacement at the cracks, or floor cracks that align with wall cracks, can indicate a problem. Floors that are tipped and cracked need to be evaluated. Floors that are heaved and cracked are a problem.

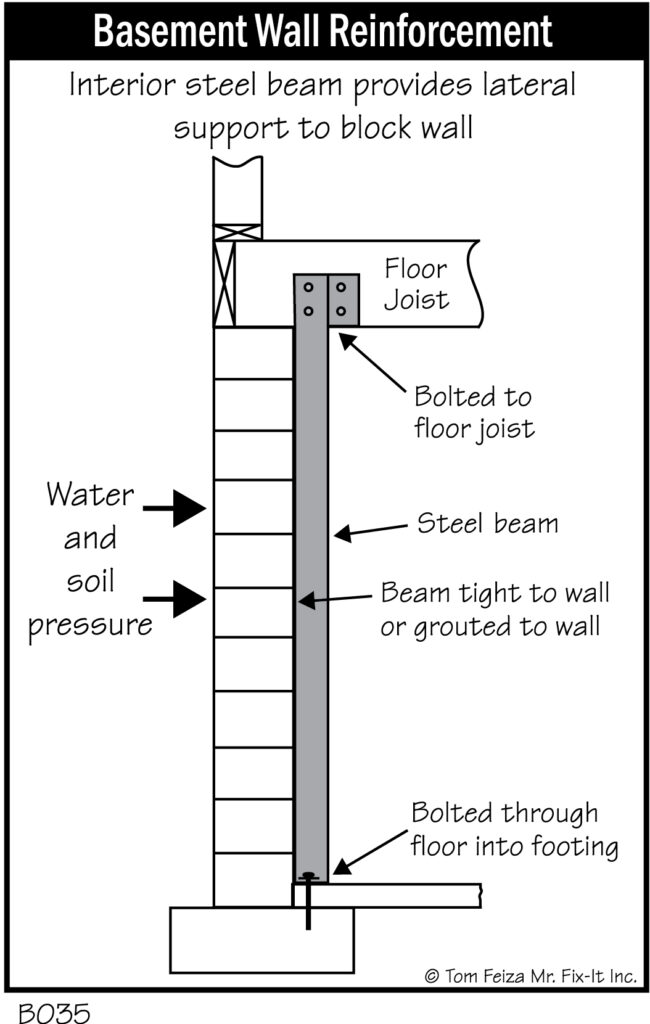

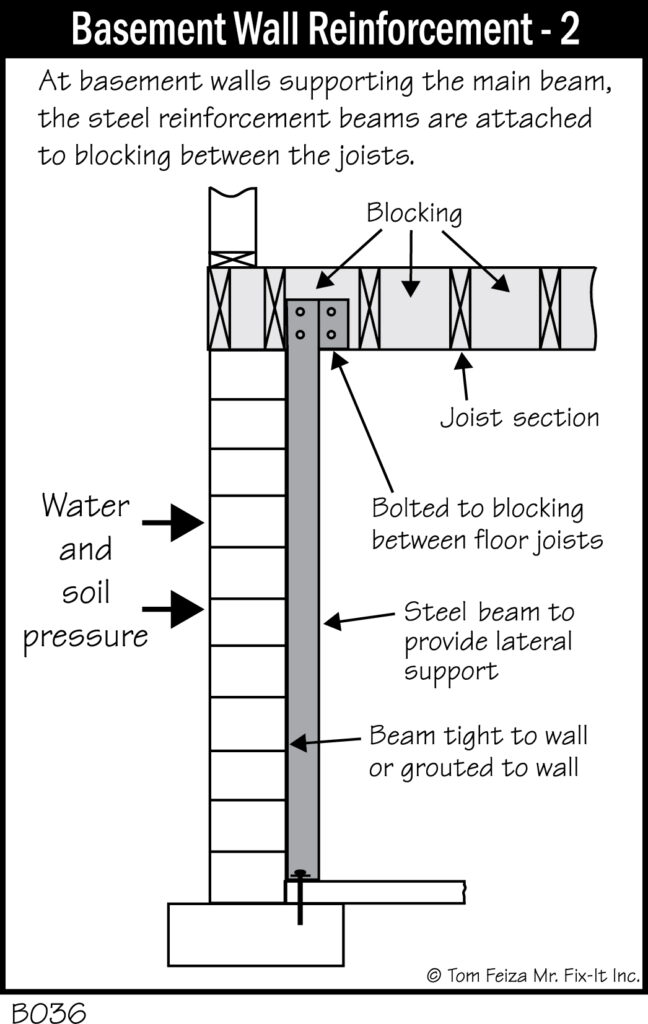

Repair Beams for Walls

While basement wall repair can be accomplished with various techniques, a common repair for walls with minimal displacement is an interior steel beam. Illustrations B035 and B036 depict a common beam repair. The beams are bolted to the floor framing and the concrete floor and set tight to the wall. If the floor is being cut, the beams may be set into the concrete. The gap between the wall and the beam is filled with grout.

The beams are bolted to the side of the floor joists on a supporting foundation wall. When placed on a beam-end wall with joists parallel to the wall, they will be blocked back to several joists and to the subfloor for support. The beams are placed with 36- to 48-inch spacing and are cut and fabricated around obstructions. For serious displacement, an engineer should design the beam repair. Excavation and straightening of the wall may be necessary.

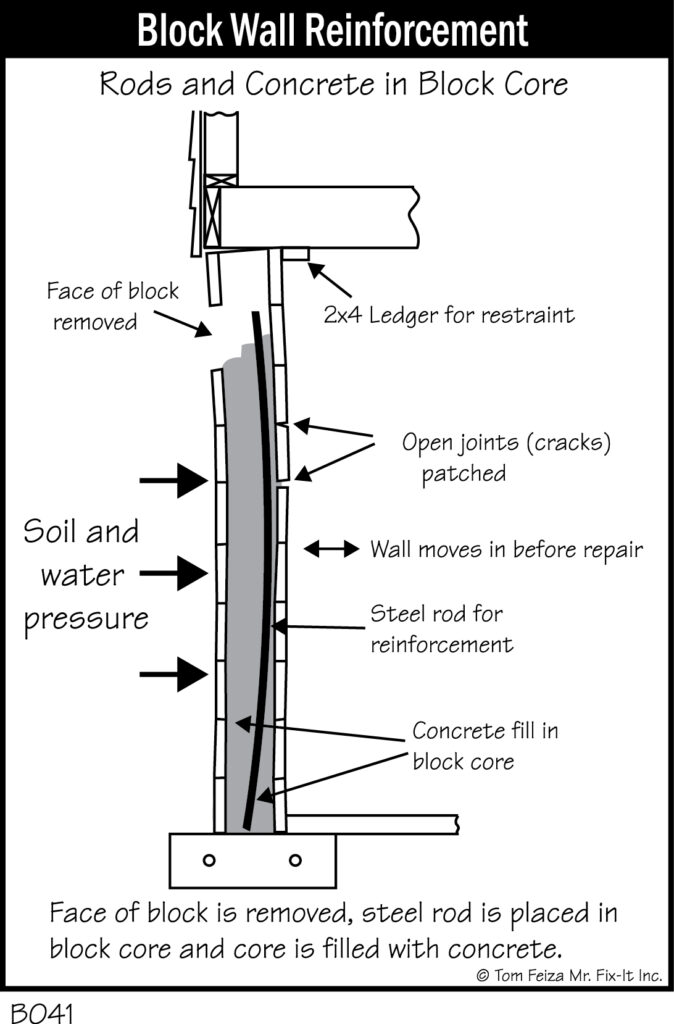

Repair With Rods and Concrete

Block walls with cracks and displacement may also be repaired and reinforced with rods and concrete. Since the typical block has hollow cores, these cores can be reinforced with vertical reinforcing rods set in concrete. The exterior face of the block is broken away, and rods are pushed down the core. Concrete is then poured down the core.

This repair method is difficult to implement because it is hard to control the placement of the rods and the concrete. The rod and reinforcement concrete also does not extend into the top block.

If patches are visible in the face of the exterior top blocks, a repair was probably done with rods and concrete.

Approaching Basement Cracks

As a homeowner, you should periodically look for cracks and movement in basement walls and floor. If you see movement or other changes, call in a professional.

You can also monitor cracks several ways. Take a picture of a crack with a date clearly showing. Use the picture to compare the movement from year to year. The history of movement is very important. At times walls crack and then remain stable for many years, reducing reason for concern.

You can monitor cracks with masking tape. Firmly place a piece of masking tape perpendicular over a crack and cut it with a razor blade at the crack. Then watch for movement of the tape. You may see the cut open and close or the edges of the tape move up and down.

You can fill cracks with mortar (called re-pointing or tuck pointing). After repair, the cracks can then be monitored for further movement or cracking. However, filling the crack will not allow it to close as conditions change – another potential problem.

You can also measure movement and displacement with a plumb bob, as described earlier. Hang a weight from a string near the basement wall. Measure from the string to the wall. The string will be vertical, and variations in the measurements to the edge of the wall signal wall movement. Be careful, however – some walls are built out of plumb, so check the corners first. Corners usually don’t move and will indicate how straight the wall was originally. If a corner is 3/4 inch out of plumb, the whole wall may be out of plumb from the original construction.

When to Call in a Professional

When you notice movement and cracks, or any movement over 1/2 inch, get professional advice. But don’t be overly concerned, and don’t rush. Take a few deep breaths and don’t panic. Take time to investigate and evaluate. Educate yourself about basements. The key is the type of movement and location of the cracks. Unless the failure and cracks are catastrophic, they took several years to develop, and you have some time to consider corrective work.

Evaluating your walls is confusing and difficult. You should consider calling in a structural engineer or independent consultant who is not selling repair services. Talk to the consultants about their experience and background. Check references. A consultant who designs structural steel or parking structure repairs may not be the person for your basement.

If a repair is required, a consultant can provide specifications for contractors to follow – a great way to get accurate, competitive bids. An independent consultant has no reason to recommend a repair unless it is really needed.

How to Hire a Contractor

Don’t jump at the first repair proposal, and don’t fall for high-pressure sales tactics. Don’t fall for the cheap price. There are many reputable basement repair contractors; you need to find one. Ask friends for recommendations, or look for a contractor through a builders’ or home repair professionals’ organization. Look for a contractor who has been in business for a number of years and has a good track record. Do check references.

Contractors should provide proof of insurance – liability and workers’ compensation. A repair contract in writing should be offered, and liens and wavers should be explained fully. Contractors should be knowledgeable about building codes and requirements. Most municipalities require a permit for a basement repair, and a licensed plumber is required for sump pump installation. Often, to obtain a permit for major repairs, an engineer must design them. Make sure the contractor is responsible for permits and that your municipality provides the required inspections.

Final Words of Basement Wisdom

A basement problem is an evolution, not an event. You see one event of a crack or other symptom at one point in time. The history and future are equally important in evaluation and repair. Take that deep breath and don’t panic. Take time to select professionals you trust to help solve a basement problem. The appearance of seepage or a new crack does not necessarily mean you have a major problem – it does mean you need to address maintenance and take a critical look at your basement.

Remember that at some point, most of us sell or buy a home. If you maintain your basement, most serious problems can be prevented. If a problem occurs, keep good records and disclose this information in the process of selling your home. All buyers and professional consultants will value accurate information concerning basement conditions, and it will simplify selling your home.